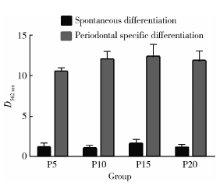

目的 研究不同代次诱导多能干细胞(induced pluripotent stem cells,iPSCs)在增殖及向牙周定向分化能力上的区别,为今后深入研究和可能的临床应用提供理论基础。方法 复苏不同代次(P5、P10、P15、P20)人牙龈成纤维细胞来源的iPSCs,观察细胞形态并比较其增殖能力,进一步将各代次细胞形成拟胚体,于含生长分化因子-5(growth/differentiation factor-5, GDF-5)的培养基中诱导分化14 d,同时分别设置未诱导自发分化组为阴性对照,茜素红染色观察矿化结节并半定量分析钙盐沉积量,qRT-PCR及免疫荧光染色分别检测牙周相关基因及蛋白的表达,评价各代次间分化能力的差异。结果 不同代次的iPSCs均具有很强的体外增殖能力,经牙周定向诱导的细胞呈成纤维细胞样生长,茜素红染色可形成“矿化”结节,细胞钙盐沉积量较自发分化组显著增高且差异有统计学意义(P5: t=2.125, P=0.003;P10: t=2.246, P=0.021;P15: t=3.754, P=0.004;P20: t=3.933, P=0.002),但相同诱导条件下不同代次间钙盐沉积量差异无统计学意义(牙周定向诱导组: F=2.365, P = 0.109;自发分化对照组: F=2.901, P=0.067),此外,相同代次细胞中诱导组牙周相关标记物的表达均高于对照组且差异有统计学意义( P<0.05),但不同代次间的蛋白表达差异无统计学意义(骨涎蛋白: F=0.9267, P=0.450;波形蛋白: F=0.9171, P=0.455;牙骨质蛋白1: F=2.129, P=0.137)。结论 不同代次不会影响iPSCs的增殖及分化能力,体外长期培养的iPSCs易于扩增,较高代次者经诱导仍可高效定向分化,适合作为牙周组织工程的种子细胞。

Objective: To compare the proliferative and periodontal specific differentiation abilities of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) at different passages, and to investigate whether long term culturing would have a negative influence on their proliferation and specific differentiation capacity, thus providing a theoretical basis for further in-depth research on periodontal regeneration and the possible clinical applications of iPSCs.Methods: IPSCs derived from human gingival fibroblasts at passages 5, 10, 15 and 20 were recovered and cultured in vitro. Their morphology and proliferation rates were observed respectively. We further induced the iPSCs at different passages toward periodontal tissue under the treatment of growth/differentiation factor-5 (GDF-5) for 14 days through the EB routine, then compared the periodontal differentiation propensities between the different passages of iPSCs by detecting their calcified nodules formation by Alizarin red staining and assaying their relative periodontal tissue related marker expressions by qRT-PCR and immunofluorescence staining, including bone related markers: osteocalcin (OCN), bone sialoprotein (BSP); periodontal ligament related markers: periostin, vimentin; and cementum related markers: cementum attachment protein (CAP), cementum protein 1 (CEMP1). The untreated spontaneous differentiation groups were set as negative controls respectively.Results: iPSCs at different passages all showed a high proliferative capacity when cultured in vitro and turned into a spindle-like shape similar to fibroblasts upon periodontal specific differentiation. All iPSCs formed typical calcified nodules upon GDF-5 induction by Alizarin red staining in comparison to their untreated controls. The relative calcium deposition at all passages had been significantly upgraded under the treatment of GDF-5 (P5: t=2.125, P=0.003; P10: t=2.246, P=0.021; P15: t=3.754, P=0.004; P20: t=3.933, P=0.002), but no significant difference in their calcium deposition were detected within passages 5, 10, 15 and 20 (periodontal differentiation: F=2.365, P=0.109; spontaneously differentiation: F=2.901, P=0.067). Periodontal tissue related marker expressions of iPSCs at all passages had also been significantly upgraded under the treatment of GDF-5 ( P<0.05), but still, no significant difference in their expression levels of periodontal tissue related proteins were detected within passages (BSP: F=0.926 7, P=0.450; vimentin: F=0.917 1, P=0.455; CEMP1: F=2.129, P=0.1367).Conclusion: Our results preliminarily confirmed that long term culturing won’t influence the proliferation capa-city and periodontal specific differentiation propensity of iPSCs, as they can still proliferate and differentiate toward periodontal cells with high efficiency upon growth factor induction after continuous passaging. Therefore, iPSCs could be recognized as a promising cell source for future possible application in periodontal tissue regeneration.

牙周支持组织(包括牙槽骨、牙周膜及牙骨质)的修复再生一直是牙周治疗的瓶颈, 传统的引导性组织再生术等临床手段难以在组织学上形成新生的牙周膜纤维, 并嵌入相邻的新生牙骨质及牙槽骨[1]。近年来组织工程的兴起为实现真正意义上的牙周支持组织再生提供了全新的思路及方法, 即将干细胞体外分离培养、扩增后诱导分化, 与支架材料结合制备成复合物再植入牙周缺损部位[2]。目前组织工程的干细胞类型主要包括胚胎干细胞(embryonic stem cells, ESCs)和成体干细胞(adult stem cells, ASCs)[3]。由于存在伦理争议和免疫排斥风险, 胚胎干细胞的应用一直受到很大限制[3], 而以间充质干细胞为代表的成体干细胞也存在着长期培养后细胞老化、增殖分化能力大幅降低的缺点[4]。2006年, Takahashi等[5]将4种转录因子导入小鼠成纤维细胞, 重编程后获得与胚胎干细胞在表型、生长特性、基因表达和分化潜能方面高度相似的诱导多能干细胞(induced pluripotent stem cells, iPSCs), 由于其增殖分化方面存在巨大潜力, 同时可避免异体免疫排斥和伦理问题, 目前已被视为新一代理想种子细胞。

组织重建需要大量优质种子细胞的移植, 治疗前需在体外多次传代扩增以保证其数量需求, 但如前文所述, 成体干细胞与终末分化的体细胞一样, 在体外培养扩增的过程中易于老化, 多次传代后增殖速度明显减慢, 分化潜能普遍降低[6, 7, 8], 因此一般原则上优先选用增殖及分化能力较强的早代次细胞, 但代次对诱导多能干细胞增殖分化潜能影响的研究目前在国内尚未见报道, 国际上关于多次传代对iPSCs分化倾向影响的研究亦少见, 且尚无定论[9, 10, 11, 12] 。种子细胞的优化与否将直接关系到细胞治疗的质量及安全, 因此体外长期培养的iPSCs是否存在结构和功能上的变异对疾病建模及未来可能的临床应用均有重要意义。

多项研究表明, 生长分化因子-5(growth /dif-ferentiation factor-5, GDF-5)可显著促进牙周膜细胞的增殖[13], 同时具有促进牙周组织愈合及再生的潜能[14, 15]。本课题组既往的研究已证实GDF-5于体内、外均能促进iPSCs向成骨、成纤维和成牙骨质3个方向分化, 并已通过比较不同浓度梯度作用下细胞分化的能力, 摸索出最适宜的诱导浓度为200 μ g/L[16]。本研究比较了不同代次人牙龈成纤维细胞来源iPSCs的形态特点及增殖能力, 进一步通过GDF-5诱导各代次细胞向牙周定向分化, 设未诱导自发分化组为阴性对照, 利用茜素红染色评价成骨分化的能力, qRT-PCR及免疫荧光染色比较各代次分化细胞成骨、成牙周膜、成牙骨质的相关基因及蛋白的表达, 探究代次高低对人牙龈来源iPSCs增殖及牙周定向分化潜能的影响, 为诱导多能干细胞能否做为牙周再生治疗的理想种子细胞提供更加充实的依据。

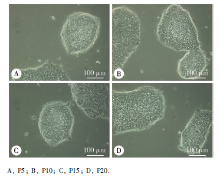

本课题组既往已于北京大学干细胞研究中心将人牙龈成纤维细胞成功诱导为iPSCs并于体外连续传代、扩增, 同时冻存保种[16]。现分别复苏第5, 10, 15, 20代iPSCs, 解冻后1 000 r/min离心5 min以去除冻存液中的二甲基亚砜(dimethyl sulfoxide, DMSO), 将细胞接种于0.5%(体积分数)Matrigel包被的培养皿中, 加入PSCeasy多潜能干细胞培养基, 37 ℃, 5%CO2培养箱中培养, 每天换液, 光学显微镜下观察细胞形态。

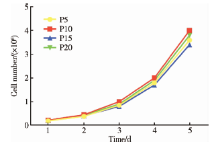

分别取生长状况良好的第5、10、15、20代人iPSCs, 经乙二胺四乙酸(ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid, EDTA)消化制成单细胞悬液计数, 调整细胞浓度为2× 105/mL接种于24 孔板内, 每孔1 mL, 每组3孔, 置37 ℃, 5%(体积分数)CO2培养箱中培养, 每隔24 h收集每组3孔细胞, 分别计数活细胞并取平均值。一次传代内连续测定5 d, 以培养时间为横坐标, 以细胞数量(× 106/mL)为纵坐标绘制生长曲线。

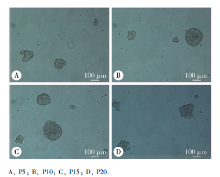

1.4.1 拟胚体(embryonic bodies, EBs)的获得 5 d 后细胞克隆即增殖到约80%融合, EDTA 37 ℃消化2~3 min吹打成细胞悬液, 以1× 105/皿的密度均匀接种于未铺胶的悬浮培养皿, 其中EB培养基为DMEM/F12(含体积分数20%血清替代物、0.1% β -巯基乙醇, 1% L-谷氨酰胺、1%非必需氨基酸), 37 ℃5%(体积分数)CO2培养箱中继续培养3~5 d, 隔天换液。

1.4.2 牙周定向诱导 将拟胚体接种于0.5% (体积分数)Matrigel包被过的培养皿中, 每皿接种约15个拟胚体, 牙周诱导培养基为DMEM/F12(含体积分数20%胎牛血清及200 μ g/L rhGDF-5), 同时设置未诱导的自发分化组作为阴性对照, 培养基为DMEM/F12(含体积分数20%胎牛血清), 均于37 ℃, 5%(体积分数)CO2培养箱中培养14 d, 隔天换液。

各代次诱导组及对照组分化14 d后, 弃培养液, PBS洗3遍, 4%(质量分数)多聚甲醛固定30 min, PBS漂洗3遍, 1%(质量分数)茜素红溶液(pH=4.5)常温染色20 min, PBS漂洗3遍, 光学显微镜下直接观察矿化结节的形成。

PBS孵育15 min后弃上清, 加入100 mmol/L氯化十六烷基吡啶, 室温下孵育1 h溶解矿化结节。分光光度计检测562 nm处上清的光密度值; 氯化十六烷基吡啶溶液调零, 同时测定一组未加茜素红的单纯细胞上清液光密度值, 最终样本测定值=含茜素红上清光密度值-单纯细胞光密度值, 每个样本重复3次, 比较各代次间钙盐沉积量的差异。

1.6.1 细胞RNA提取 各代次诱导组及对照组分化14 d后, 使用RNeasy MiNi Kit试剂盒提取各样本的RNA。

1.6.2 RNA质量检测 使用无RNA酶H2O将分光光度计调零, 取1 μ L RNA溶液加入49 μ L无RNA酶H2O充分混匀, 分光光度计上读取260 nm与280 nm处光密度的比值, 以确定RNA溶液的纯度, 比值范围为1.8~2.1。

1.6.3 mRNA反转录 PrimeScriptTM RT Master Mix试剂盒进行RNA反转录, 得到的cDNA保存于-20 ℃中待用。

1.6.4 实时定量聚合酶链式反应 实时荧光定量PCR检测各样本向牙周方向分化过程中相关基因的表达, 包括成骨方向的骨钙蛋白(osteocalcin, OCN)和骨涎蛋白(bone sialoprotein, BSP), 成牙周膜结缔组织方向的骨膜蛋白(periostin)和波形蛋白(vimentin), 以及成牙骨质方向的牙骨质附着蛋白(cementum attachment protein, CAP)和牙骨质蛋白1(cementum protein 1, CEMP1)[17, 18, 19]。按20 μ L总反应体系加入上下游引物(表2)、cDNA模板及各反应试剂, 包括SYBR® Premix Ex TaqTM 10 μ L, 上下游引物各0.8 μ L, ROX Reference Dye(50× )0.4 μ L, 模板2 μ L, 6 μ L dH2O补齐, 充分混匀, 利用cDNA作为模板扩增牙周特异性基因, GAPDH作为对照。

| 表2 人牙周相关基因引物序列 Table 2 List of primer sequences used for qRT-PCR |

分化第14天, 诱导组及对照组各代次细胞用4%(质量分数)多聚甲醛固定15 min, 0.2%(质量分数)Tritonx 100室温反应15 min, 3%(质量分数)牛血清白蛋白(BSA)封闭30 min。分别加入1 ∶ 100稀释的第一抗体, 包括抗骨涎蛋白抗体 (anti-bone sialoprotein antibody)、抗波形蛋白抗体 (anti-vimentin antibody) 和 抗牙骨质蛋白1抗体 (anti-CEMP1 antibody), 4 ℃孵育过夜。PBS洗3次, 每次10 min, 分别加入1 ∶ 200稀释的第二抗体, 包括FITC标记山羊抗兔IgG及Alexa Fluor®488标记山羊抗小鼠IgG, 37 ℃避光孵育2 h。细胞核用VECTASHIELD®Mounting Media with DAPI染色, 激光共聚焦扫描显微镜观察拍照, Image J软件分析, 比较各代次荧光强度的差异。

使用SPSS 19.0软件进行统计学分析, 计量资料的描述用均数± 标准差表示, 对于相同培养条件下4组不同代次的细胞, 采取单因素方差分析和Student Newman Keuls(SNK)法两两比较; 对于相同代次细胞在诱导组和对照组间的比较采用双侧t检验, P< 0.05认为差异有统计学意义。

复苏后的人iPSCs多于1~2 h内贴壁, 各代次细胞增殖迅速, 第5~6天融合度即达80%。各代次iPSCs在无饲养层细胞培养条件下均贴壁良好, 呈克隆集落样生长, 结构均匀, 形态典型, 多呈岛状或巢状。

生长曲线显示, 第5、10、15及20代人iPSCs体外扩增的速度相似, 在一次传代内均未出现平台期, 为快速增长型细胞, 群体倍增时间约为24 h。细胞均有较强的分裂增殖能力, 其中以第10代增殖能力最强、第15代增殖能力稍弱, 但各时间点的细胞数目差异无统计学意义(P> 0.05), 表明人iPSCs在多次传代后仍可保持较高增殖活性。

各代次人iPSCs均可形成相近数量和大小的拟胚体, 贴壁后随分化时间延长, 细胞形态由克隆细胞簇渐变为成纤维样细胞集落, 呈长梭形或多角形平行排列或旋涡状生长, 逐渐汇集, 最终连接成片。

第5、10、15、20 代人iPSCs经牙周定向诱导14 d后, 茜素红染色均可见较多“ 矿化” 结节形成, 界限较清, 外围呈橘红色, 中心呈深褐色, 而自发分化对照组几乎未见矿化结节生成。钙含量半定量结果显示, 相同代次的细胞中, 诱导组表达均高于对照组, 且差异有统计学意义(P5:t=2.125, P=0.003; P10:t=2.246, P=0.021; P15:t=3.754, P=0.004; P20:t=3.933, P=0.002), 但相同诱导条件下, 不同代次细胞(P5、P10、P15、P20)在562 nm处平均光密度值的差异无统计学意义(牙周定向诱导组:F=2.365, P=0.109; 自发分化对照组:F=2.901, P=0.067), SNK法进一步两两比较, 任意两组间差异无统计学意义。

| 图5 不同代次人iPSCs牙周定向诱导14 d后的茜素红染色Figure 5 Alizarin Red staining of iPSCs at different passages upon periodontal differentiation |

第5、10、15、20 代人iPSCs分别自发分化及牙周定向诱导14 d后, qRT-PCR检测牙周相关基因表达, 包括成骨方向的骨钙素及骨涎蛋白, 成牙周膜结缔组织方向的骨膜蛋白及波形蛋白, 成牙骨质方向的牙骨质附着蛋白及牙骨质蛋白1, 结果显示骨膜蛋白在对照组亦有较高表达, 但相同代次的细胞中诱导组各牙周相关基因的表达均高于对照组, 且差异有统计学意义(P< 0.05)。诱导组细胞在第15代成骨相关基因、第10代成牙周膜相关基因及第20代成牙骨质相关基因的mRNA表达水平上较其他代次偏低, 在培养条件一定的前提下, 不同代次细胞(P5、P10、P15、P20)间mRNA的相对表达水平间差异无统计学意义(表3)。

| 图7 qRT-PCR检测诱导组及对照组不同代次iPSCs牙周相关基因的相对表达Figure 7 The relative periodontal tissue gene expression of spontaneous and periodontal differentiated iPSCs at different passages by qRT-PCR |

| 表3 不同代次细胞间牙周相关基因相对表达的单因素方差分析结果 Table 3 The univariate analysis results of relative periodontal tissue gene expression of iPSCs at different passages |

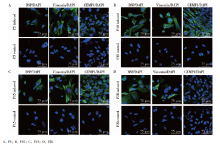

第5、10、15、20代iPSCs经牙周定向诱导分化14 d后, 牙周相关蛋白BSP、 波形蛋白及CEMP1染色均为阳性, 细胞质呈绿色荧光, 细胞核经DAPI染色呈蓝色荧光。对照组中仅第5及15代波形蛋白染色呈弱阳性, 这与同为牙周膜相关标记的骨膜蛋白在自发分化组有较高表达的qRT-PCR结果趋于一致; Image J软件分析相同代次细胞中, 诱导组各牙周相关蛋白荧光强度均高于对照组, 且差异有统计学意义(P< 0.05); 在诱导组中第20代CEMP1荧光偏弱, 不同代次细胞(P5、P10、P15、P20)间荧光强度的差异并无统计学意义(BSP:F=0.927, P=0.450; vimentin:F=0.917, P=0.455; CEMP1:F=2.129, P=0.137)。

iPSCs因理论上具有无限自我更新的能力和分化为三胚层细胞的多能性, 同时绕开了胚胎干细胞研究面临的伦理争议和免疫排斥问题, 为细胞移植[20]、疾病建模[21]以及发育研究[22]等提供了全新的方法和手段, 自诞生以来, 其分化的功能细胞已在镰状细胞性贫血[23]、帕金森病[24]等动物模型上成功实现了组织再生, 关于iPSCs向心肌细胞、肝细胞等方向分化的研究也已取得了进展[25], 但其在牙周再生方面的研究尚处于起始阶段。

在组织再生的三要素中, 除细胞因子及生长支架的选择外, 种子细胞的优化也至关重要。目前, 细胞代次对分化潜能影响的研究主要集中在以间充质干细胞为代表的成体干细胞方面:受培养条件及环境限制, 成体干细胞体外传代至一定代次后增殖和分化能力均明显降低, 其生物学不稳定性严重限制了进一步的推广应用。成体干细胞随培养时间延长呈现衰老的现象已引起普遍关注, 但细胞代次对iPSCs分化潜能及倾向影响的研究国际上却较少见且尚无定论, 在国内目前尚未见相关研究。

尽管诱导多能干细胞和胚胎干细胞在结构和功能上极其相似[26], 基因复制数的改变、点突变、DNA不完全去甲基化和异常的重新甲基化等[27, 28, 29, 30, 31]均会导致iPSCs与ESCs在表观遗传修饰[32]、基因表达[33]和分化潜能[34] 等方面存在不同程度的细微差异。2010年, Kim等[11]经CHARM甲基化分析发现iPSCs与ESCs的表观遗传学差异有一部分原因是不完全重编程导致遗留有少量供体组织遗传信息, 并将该现象命名为表观遗传记忆(epigenetic me-mory), 多项研究表明该性质将影响细胞的全能性(即发育为完整个体的能力)[35], 使iPSCs更倾向于向供体来源的方向分化[34, 36, 37, 38]。

Polo等[10]将不同组织来源的iPSCs在相同培养条件下连续传代, 结果显示虽然不同代次iPSCs增殖速度均较快且差异无统计学意义, 但其与ESCs的差异性甲基化区域(differentially methylated regions, DMRs)数目却随代次增加而逐渐减少, 进而提出猜想:连续传代会逐渐擦除早代次iPSCs携带的供体细胞表观遗传学信息, 进而可能影响其分化倾向, 但不同组织来源iPSCs消除与ESCs间差异需要的传代次数不同, 其具体分子机制亦不明确。

Nishino 等[9]比较了5种不同组织来源的iPSCs与ESCs的甲基化谱, 发现其中一些组织来源的iPSCs与ESCs间差异性甲基化的基因位点数目在第40代时较早期代次有不同程度的减少, 但这一现象并未出现在所有克隆中。Kim等[11]认为培养时间也许会影响某些特定的基因位点, 但并不适用于整个基因组和所有iPSCs细胞系。Lister等[12]的甲基化分析结果则表明, 较早代次(第15代)及较晚代次(第65代)iPSCs与ESCs的差异性甲基化数目基本没有变化。

造成以上结论不一致的原因可能有如下几个方面:首先, 诱导多能干细胞对外界环境很敏感, 即使相同的培养条件, 不同实验室中细胞的生物学状态也有差异; 其次, 除细胞代次外, 组织来源[10]、克隆质量[39, 40]、不同遗传背景的供体[41, 42]均可能影响iPSCs的表观基因组进而影响其分化倾向; 最后, 定向诱导前形成拟胚体的质量、大小及接种密度也会对最终的分化效果造成影响。总之, iPSCs的表观遗传记忆能否通过多次传代的方式被擦除存在较大争议, 因此连续传代是否会影响iPSCs的分化倾向亦不明确。

本研究中人牙龈成纤维细胞源iPSCs传代至第20代后, 光学显微镜下观察形态良好, 依旧保持着旺盛的生长状态, 说明体外长期培养的iPSCs无明显衰老迹象。经牙周定向诱导后, 茜素红染色半定量分析、qRT-PCR及免疫荧光染色等检测结果表明, 第5、10、15、20代人iPSCs在成骨、成牙周膜及成牙骨质三个方向的指标虽有细微变化, 但差异无统计学意义, 较高代次的人iPSCs依然维持着高效分化的干细胞特性。如前文所述, 与成体干细胞相比, iPSCs作为与胚胎干细胞具有相似遗传背景及生物学特性的全能干细胞, 理论上具有无限增殖及分化的全能性, 本实验的结果也初步验证了这一点, 即代次可能不会对人iPSCs的增殖及分化能力造成影响, 提示在实际应用中可以通过多次传代的方式获得数量充足的优质种子细胞。

本研究在细胞及分子水平上得出牙龈来源的人iPSCs在多次传代后牙周定向分化能力相当的结论, 但在基因水平还可进一步行甲基化分析, 探究不同代次人iPSCs与ESCs的差异性甲基化位点数目及分布; 如有条件, 该研究需通过比较多种细胞来源iPSCs向不同组织方向定向分化的潜能加以完善; 此外, 虽然体外实验表明人iPSCs具有较高的向牙周方向定向分化的潜能[16], 其能否实现真正意义上的牙周再生还需结合载体支架形成复合体, 移植入动物体内在组织学水平加以佐证[2, 43]; iPSCs牙周定向分化的具体分子生物学机制(如信号通路等)同样尚待进一步探索。相信随着未来研究的不断深入, 人iPSCs将更好地发挥它在科研和临床中的作用, 为早日实现牙周组织再生提供可能。

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

| [1] |

|

| [2] |

|

| [3] |

|

| [4] |

|

| [5] |

|

| [6] |

|

| [7] |

|

| [8] |

|

| [9] |

|

| [10] |

|

| [11] |

|

| [12] |

|

| [13] |

|

| [14] |

|

| [15] |

|

| [16] |

|

| [17] |

|

| [18] |

|

| [19] |

|

| [20] |

|

| [21] |

|

| [22] |

|

| [23] |

|

| [24] |

|

| [25] |

|

| [26] |

|

| [27] |

|

| [28] |

|

| [29] |

|

| [30] |

|

| [31] |

|

| [32] |

|

| [33] |

|

| [34] |

|

| [35] |

|

| [36] |

|

| [37] |

|

| [38] |

|

| [39] |

|

| [40] |

|

| [41] |

|

| [42] |

|

| [43] |

|