目的 研究类瓷树脂和两种玻璃陶瓷牙合贴面在咀嚼和温度疲劳后牙合接触区的磨耗程度及表面粗糙度的变化,优选对临床有指导意义的牙合贴面材料。方法 将24颗完整的离体人前磨牙预备成牙合面中重度磨耗的形态,轴壁釉质完整、牙尖斜度20°。制作1.5 mm厚的类瓷树脂、热压铸造二硅酸锂增强型玻璃陶瓷(热压铸瓷)、计算机辅助设计/计算机辅助制造(computer-aided design/computer-aided manufacturing, CAD/CAM)切削二硅酸锂增强型玻璃陶瓷(CAD/CAM切削瓷)牙合贴面。使用树脂粘接剂将牙合贴面粘接到预备体牙合面形成试件,在水中储存 72 h后在咀嚼模拟疲劳机上进行模拟5年口内温度疲劳和咀嚼疲劳的实验(5~55 ℃冷热水循环,模拟后牙咀嚼循环120万次)。用三维激光模型扫描和数字化分析法评价疲劳实验前后牙合贴面的磨耗程度,用三维形貌测量激光显微镜观察其表面形态及粗糙度变化。使用单因素方差分析方法对结果进行统计学分析,以 P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。结果 咀嚼和温度疲劳实验后没有试件发生脱粘接或折裂。类瓷树脂组、热压铸瓷组、CAD/CAM切削瓷组的平均磨耗为(-0.13±0.03) mm、(-0.05±0.01) mm和(-0.05±0.01) mm,类瓷树脂组的磨耗量显著大于玻璃陶瓷两组( P<0.001);疲劳实验前各组牙合接触区的表面粗糙度(Ra)为(1.24±0.20) μm、(0.75±0.09) μm、(0.73±0.14) μm,类瓷树脂组的表面粗糙度显著高于玻璃陶瓷两组( P<0.001);疲劳实验后的表面粗糙度为(1.81±0.24) μm、(1.53±0.26) μm及(1.77±0.23) μm,热压铸瓷组显著低于类瓷树脂组( P=0.005)及CAD/CAM切削瓷组( P=0.010)。结论 从磨耗速度来看,类瓷树脂牙合贴面显著高于两种玻璃陶瓷,但更接近于对颌牙为天然牙时牙釉质的平均磨耗速度;从表面粗糙度来看疲劳实验前类瓷树脂的表面粗糙度显著高于两种玻璃陶瓷,疲劳实验后热压铸瓷牙合贴面的表面粗糙度最低。

Objective: To evaluate the wear intensity and surface roughness of occlusal veneers on premolars made of microhybrid composite resin or two kinds of ceramics in vitro after the thermocycling and cyclic mechanical loading tests.Methods: In the study,24 fresh extracted human premolars without root canal treatment were prepared (cusps reduction of 1.5 mm in thickness to simulate middle to severe tooth wear, the inclinations of cusps were 20°). The prepared teeth were restored with occlusal veneers made of three different materials: microhybrid composite, heat-pressed lithium disilicate ceramic and computer-aided design/computer-aided manufacturing (CAD/CAM) lithium disilicate ceramic in the thickness of 1.5 mm. The occlusal veneers were cemented with resin cement. The specimens were fatigued using the thermocycling and cyclic mechanical loading tests after being stored in water for 72 h. The wear of specimens was measured using gypsum replicas and 3D laser scanner before and after the thermocycling and cyclic mechanical loading tests and the mean lost distance (mm) was used to indicate the level of wear. The surfaces of occlusal contact area were observed and the surface roughness was recorded using 3D laser scanning confocal microscope before and after the fatigue test. Differences between the groups were compared using ONE-way ANOVA( P<0.05).Results: All the specimens successfully survived after the thermocycling and cyclic mechanical loading tests. The mean wear of microhybrid composite group, heat-pressed lithium disilicate ceramic group, and CAD/CAM lithium disilicate ceramic group was (-0.13±0.03) mm, (-0.05±0.01) mm and (-0.05±0.01) mm, the wear of microhybrid composite was significantly higher than the two ceramic groups( P<0.001).The mean surface roughness(Ra)before the fatigue test was(1.24±0.20) μm, (0.75±0.09) μm, (0.73±0.14) μm and it became (1.81±0.24) μm, (1.53±0.26) μm and (1.77±0.23) μm after the test . Before the fatigue test, the surface roughness of microhybrid composite was significantly higher than the two ceramic groups( P<0.001) and after the test, the surface roughness of heat-pressed lithium disilicate ceramic was significantly lower than microhybrid composite( P=0.005) and CAD/CAM lithium disilicate ceramic( P=0.010).Conclusion: From the view of wear speed, microhybrid composite was significantly higher than the two kinds of ceramics, but it was similar to enamel when the opposing tooth was natural. The surface roughness before the themocycling and cyclic mechanical loading test of microhybrid composite was significantly higher than that of the two ceramic groups. After the test, the surface roughness of heat-pressed ceramic was significantly lower than that of the other two groups. From the view of surface roughness, heat-pressed ceramic has more advantage.

中重度磨耗牙主要由酸蚀、磨损、磨牙症等原因引起, 通常会导致咬合垂直距离的降低和牙本质敏感, 可能会造成口颌系统功能异常并带来美学问题。为了得到修复空间, 通常需要升高咬合垂直距离。传统的修复方式有牙合垫、可摘局部义齿、全冠等。

近年来, 随着粘接修复的发展, 牙合贴面的使用越来越普及, 临床上可以使用牙合贴面来修复中重度磨耗牙。采用牙合贴面修复中重度磨耗牙可以减少不必要的牙体组织磨除, 尽量保存活髓[1, 2]。有临床研究表明, 保存更多的牙体组织的患牙远期修复效果更好, 并且牙合贴面对牙龈刺激小, 继发龋发生率更小[3]。

具有中重度磨耗牙的人的牙合力可能大于具有生理性磨耗程度牙的人, 并且有磨牙症等不良习惯的可能性大, 导致修复体承受更大的咬合力[4]。修复体的耐磨耗性能对于维持长期稳定的牙合关系非常重要。天然牙与修复体的磨耗程度不同会导致口颌系统功能和美学问题[5]。早期的复合树脂耐磨耗性远低于天然牙, 随着复合树脂的发展, 其耐磨性得到了明显改善[6, 7]。

修复体的表面光滑程度也是评价修复体的重要指标。粗糙的修复体表面会带来美观问题、龋坏及牙周问题, 也会增加其对颌牙的磨耗。光滑的修复体表面还可以减少菌斑的附着[8]。上釉可以使修复体表面变得光滑、美观、卫生, 但是在修复体使用过程中, 釉层很快会消失, 因此修复体磨耗后的表面光滑程度也至关重要[9]。

临床上, 作为牙合贴面的材料, 在复合树脂中添加微细瓷成分的类瓷树脂、热压铸造二硅酸锂增强型玻璃陶瓷及计算机辅助设计/计算机辅助制造(computer-aided design/computer-aided manufac-turing, CAD/CAM)切削制造二硅酸锂增强型玻璃陶瓷都被广泛应用, 但是哪种材料更适用于临床尚缺乏足够的实验室数据及长期临床观察结果。

本研究的目的是比较类瓷树脂、热压铸造二硅酸锂增强型玻璃陶瓷及CAD/CAM切削制造二硅酸锂增强型玻璃陶瓷制作的牙合贴面在咀嚼和温度疲劳实验后牙合接触区的磨耗程度及表面粗糙度的变化, 为优选对临床有指导意义的牙合贴面材料提供理论依据。

经患者知情同意, 收集因正畸需要而拔除的完整、无龋坏、没有明显裂纹的大小相近的新鲜离体上颌前磨牙, 储存在0.02%(质量分数)的叠氮化钠溶液中, 本试验获得北京大学口腔医院生物医学伦理委员会批准。在离体牙拔除后1个月内用 0.2 mm厚的聚四氟乙烯膜包裹牙根表面, 模拟天然牙牙周膜结构, 然后将釉质牙骨质界(cemento-enamel junction, CEJ)下方3 mm以下的离体牙根包埋于甲基丙烯酸甲酯(polymethyl methacrylate, PMMA)中。

1.1.1 牙体预备 使用高速涡轮手机金刚砂钻针(DIA-BURS, MANI公司, 日本)将包埋好的离体牙牙合面平均磨除1.5 mm, 模拟中重度磨耗牙, 保证轴壁釉质完整, 颊舌尖牙尖斜度与牙合平面成20° 夹角。

1.1.2 修复体制作 将预备好的24颗离体牙随机分为3组, 每组8个, 分别制作不同材料的牙合贴面, 厚度均为1.5 mm。第1组(类瓷树脂组)牙合贴面材料为类瓷树脂(Ceramage, 松风公司, 日本), 分层堆塑并聚合(Solidilte光聚合器, 松风公司, 日本)之后上釉(Luxatemp Glazed & Bond, DMG公司, 德国); 第2组(热压铸瓷组)采用失蜡法制作热压铸造二硅酸锂增强型玻璃陶瓷(IPSe.max Press, 义获嘉伟瓦登特公司, 列支敦士登)牙合贴面并上釉(IPS e.max Ceram, 义获嘉瓦登特公司, 列支敦士登); 第3组(CAD/CAM切削瓷组)使用CAD/CAM系统(CEREC AC+MC, 西诺德公司, 德国)切削制造二硅酸锂增强型玻璃陶瓷(IPSe.maxCAD, 义获嘉伟瓦登特公司, 列支敦士登)牙合贴面并烧结及上釉(IPS e.max Ceram, 义获嘉瓦登特公司, 列支敦士登)。

1.1.3 修复体粘接 使用50 μ m的氧化铝颗粒在0.05 MPa压力下对两组玻璃陶瓷牙合贴面的组织面进行喷砂, 然后用75%(体积分数)乙醇清洁其表面, 干燥后用4.5%(体积分数)氢氟酸酸蚀30 s, 之后用预处理剂进行预处理(Porcelain Liner M, Sun Medical公司, 日本)。类瓷树脂牙合贴面的组织面直接用75%乙醇清洁表面, 干燥。牙合贴面处理完成后对所有预备体的牙釉质和牙本质进行30 s和10 s的选择性酸蚀, 然后使用自固化树脂粘接剂系统(Superbond C& B, Sun Medical公司, 日本)将牙合贴面粘固于预备体上, 并沿平行于牙长轴方向向牙合贴面施加10 N 压力, 持续5 min后清除多余粘接剂, 试件制作完成, 如图1, 试件在水中至少储存3 d后开始咀嚼和温度疲劳实验。

使用姜婷教授课题组研制的第二代咀嚼模拟疲劳实验机[10]进行咀嚼和温度疲劳实验, 模拟口内5年的疲劳情况。该咀嚼疲劳机使用弹性模量与牙釉质相似的不锈钢半球形加载头, 直径5.5 mm, 加载头垂直运动, 加载台前后方向水平运动(4 mm), 加载头随加载重量落下, 先接触颊尖舌斜面之后滑动到舌尖颊斜面, 再离开牙合面, 形成慢-快-慢-快的加载过程, 模拟后牙牙合运循环轨迹, 对试件同时进行水平向和垂直向加载, 咀嚼疲劳加载力为50 N, 加载频率1.3 Hz, 共加载120万次。温度疲劳为5~55 ℃冷热水循环, 出水时间60 s, 间隔时间12 s。

1.3.1 磨耗程度评价 咀嚼和温度疲劳前后试件分别用加成型硅橡胶(Dynamix, 贺利氏公司, 德国)取印模, 灌制超硬石膏模型(Pemaco, Pemaco公司, 美国), 用三维激光模型扫描仪(Smart Optics 880 Dental, Smart Optics公司, 德国)扫描, 使用三维检测软件Geomagic Control 2014(Geomagic公司, 美国)对疲劳实验前后试件非磨耗区进行配准(最佳拟合对齐)并分析疲劳前后牙合接触区的变化, 计算磨耗前后相差的平均距离(mm)评价牙合贴面的磨耗程度。

1.3.2 表面形态及粗糙度变化 咀嚼和温度疲劳实验前后分别用三维形貌测量激光显微镜(VK-X200, 基恩士公司, 日本)放大400倍观察牙合贴面牙合接触区的表面形态及粗糙度(Ra, μ m)。

计量数据以均数± 标准差表示, 使用SPSS 20.0软件对数据进行统计分析, 组间比较采用单因素方差分析中的Dunnett T3检验及LSD检验, 以P< 0.05为差异有统计学意义。

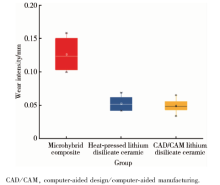

咀嚼和温度疲劳实验后没有试件发生脱粘接或折裂。类瓷树脂、热压铸瓷、CAD/CAM切削瓷组磨耗前后牙合接触区相差的平均距离分别为(-0.13± 0.03) mm、(-0.05± 0.01) mm及(-0.05± 0.01) mm, 3组间的差异有统计学意义(P< 0.001), 如图2。疲劳实验后类瓷树脂组的磨耗量显著大于玻璃陶瓷两组(Dunnett T3检验, P< 0.001)。

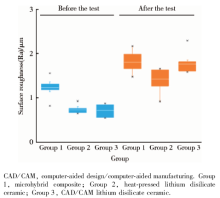

各组试件疲劳实验前后牙合接触区的表面形态如图3, 表面粗糙度如图4。不同材料疲劳实验前后表面形态各不相同。疲劳实验前类瓷树脂、热压铸瓷、CAD/CAM切削瓷组的表面粗糙度(Ra)分别为(1.24± 0.20) μ m、(0.75± 0.09) μ m、(0.73± 0.14) μ m, 3组间的差异有统计学意义(P< 0.001), 类瓷树脂组的表面粗糙度显著高于两组玻璃陶瓷(LSD检验, P< 0.001)。疲劳实验后各组的表面粗糙度均有增加, 分别为(1.81± 0.24) μ m、(1.53± 0.26) μ m及(1.77± 0.23) μ m, 3组间的差异有统计学意义(P=0.009), 以热压铸瓷组为最低(LSD检验, P=0.005, P=0.010), CAD/CAM切削瓷与类瓷树脂的差异无统计学意义(P=0.748)。

| 图3 咀嚼和温度疲劳实验前后牙合接触区的表面形态(× 400)Figure 3 Surface images of occlusal contact area before and after the thermocycling and cyclic mechanical loading test(× 400) |

本研究在体外咀嚼模拟疲劳机上模拟5年咀嚼和温度疲劳, 但修复体的磨耗过程发生在口腔环境中, 受到多种机制和多种因素影响, 例如pH值、温度、性别、饮食习惯、口腔副功能、对颌牙等[11], 很难在体外实验中准确模拟, 但体内研究耗时长且较难得出稳定的结果, 在咀嚼模拟疲劳实验机相对固定和单纯的环境中进行材料间的比较, 可以得到对临床有一定指导意义的参考理论依据[12, 13], 并且比材料学的简单磨耗试验更有临床意义。本研究采用三维激光模型扫描和数字化分析法评价疲劳实验前后牙合贴面的磨耗程度, 这种方法可以将磨耗的测量精确到10 μ m[14]。模型扫描前首先要复制试件, 本研究采用加成型硅橡胶取印模, 其尺寸变化率为 0.2%~0.3%, 用超硬石膏灌制模型, 其固化膨胀率约为0.07%, 这些变化会引起平均磨耗数值的误差, 但是本研究的主要目的是比较不同材料牙合贴面的磨耗程度, 各组牙合贴面均采用同种方法评价, 故上述复制试件的误差带来的影响较小。

本研究结果显示, 咀嚼和温度疲劳后类瓷树脂牙合贴面的磨耗量约为0.13 mm, 显著大于玻璃陶瓷牙合贴面的0.05 mm。有研究表明, 对颌为天然牙时牙合接触区的釉质磨耗速度差别很大, 平均磨耗速度为每年20~40 μ m[15, 16, 17], 根据此速度, 类瓷树脂组的磨耗速度大于天然牙釉质, 玻璃陶瓷两组小于天然牙釉质, 类瓷树脂与天然牙釉质的磨耗速度更接近。Hahnel等[18]和Han等[19]比较了不同填料的复合树脂疲劳后的磨耗程度, 发现微细填料的复合树脂耐磨耗性能较好, 与天然牙釉质的磨耗速度更相近, 与本研究结果相符。修复体的磨耗程度过大和过小都会导致口颌系统功能和美学问题, 理想的磨耗速度为与天然牙釉质的磨耗速度相近。

修复体的表面光滑程度也至关重要, Amer等[20]在关于不同瓷材料在磨耗实验后的表面粗糙度的研究中发现上釉后以及磨耗后二硅酸锂增强型玻璃陶瓷的表面粗糙度均低于普通玻璃陶瓷, Jung等[21]发现添加微细填料的复合树脂磨耗后表面粗糙度大于添加纳米填料的复合树脂。本研究的结果表明, 上釉后类瓷树脂的表面粗糙度显著高于两种玻璃陶瓷, 磨耗后3种材料的牙合贴面表面粗糙度均增加, 但热压铸瓷的表面粗糙度最低, 类瓷树脂的表面粗糙度和CAD/CAM切削瓷差异不明显, 3种材料的表面粗糙度都在可接受范围内。

综上所述, 类瓷树脂牙合贴面在咀嚼和温度疲劳实验后磨耗量显著大于两种玻璃陶瓷, 但更接近天然牙釉质的磨耗速度; 疲劳实验前类瓷树脂的表面粗糙度显著高于两种玻璃陶瓷, 疲劳实验后热压铸瓷牙合贴面的表面粗糙度最低。从磨耗速度来看, 类瓷树脂更接近于天然牙釉质, 从表面粗糙度来看, 热压铸瓷似乎更有优势。

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

| [1] |

|

| [2] |

|

| [3] |

|

| [4] |

|

| [5] |

|

| [6] |

|

| [7] |

|

| [8] |

|

| [9] |

|

| [10] |

|

| [11] |

|

| [12] |

|

| [13] |

|

| [14] |

|

| [15] |

|

| [16] |

|

| [17] |

|

| [18] |

|

| [19] |

|

| [20] |

|

| [21] |

|