1 资料与方法

1.1 数据来源

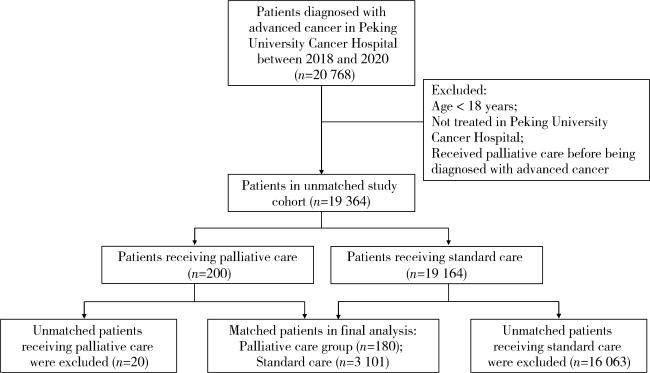

1.2 患者纳入和排除标准

1.3 患者分组与匹配

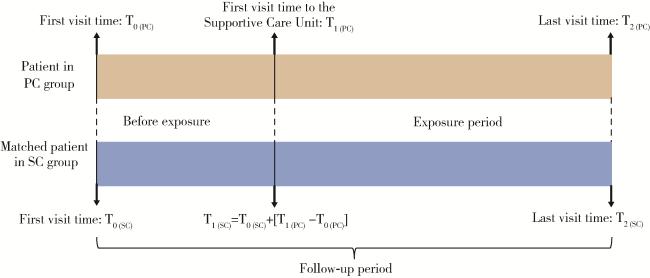

1.4 患者随访期与暴露期的确定

1.5 主要结局指标

1.6 统计学方法

2 结果

2.1 患者特征

表1 姑息治疗组与常规治疗组患者的基本特征Table 1 Characteristics of patients in the palliative care group and the standard care group |

| Items | Palliative care group (n=180) | Standard care group (n=3 101) | L1 |

| Sex | <0.01 | ||

| Female | 55 (30.6) | 1 198 (38.6) | |

| Male | 125 (69.4) | 1 903 (61.4) | |

| Age/years | 0.013 | ||

| 18-44 | 8 (4.4) | 54 (1.7) | |

| 45-64 | 75 (41.8) | 1 308 (42.2) | |

| ≥65 | 97 (53.9) | 1 739 (56.1) | |

| Location of medical insurance | 0.046 | ||

| Local | 42 (23.3) | 578 (18.6) | |

| Non-local | 138 (76.7) | 2 523 (81.4) | |

| Year of diagnosis | 0.072 | ||

| 2011-2015 | 13 (7.2) | 30 (1.0) | |

| 2016-2020 | 167 (92.8) | 3 071 (99.0) | |

| Cancer site | 0.044 | ||

| Digestive system | 80 (44.4) | 984 (31.7) | |

| Respiratory system | 19 (10.6) | 242 (7.8) | |

| Genital system | 1 (0.6) | 3 (0.1) | |

| Hematologic system | 1 (0.6) | 259 (8.4) | |

| Breast | 5 (2.8) | 13 (0.4) | |

| Head and neck | 6 (3.3) | 7 (0.2) | |

| Other sites | 6 (3.3) | 9 (0.3) | |

| Not specified | 62 (34.4) | 1 584 (51.1) |

Data are expressed as n(%). L1, multivariate imbalance measure. |

2.2 暴露前后两组患者阿片类药物使用量对比

表2 暴露前后两组患者各结局指标对比Table 2 Comparison of each outcome in the two groups before and after exposure |

| Outcomes | Before exposure | After exposure | |||||

| Palliative care group | Standard care group | P | Palliative care group | Standard care group | P | ||

| Drug use | |||||||

| Average monthly opioid consumption/DDD per person-month | 0.3 | 0.1 | <0.01 | 0.7* | 0.1 | <0.01 | |

| Medical service utilization | |||||||

| Hospital rate/% | 100.0 | 99.8 | 0.555 | 48.9* | 74.3 | <0.01 | |

| ICU rate/% | 6.7 | 2.3 | <0.01 | 1.1* | 1.6 | 0.634 | |

| Operation rate/% | 25.6 | 15.1 | <0.01 | 3.9* | 8.8 | <0.01 | |

| Medical expenditure | |||||||

| Average monthly total cost/yuan | 20 092.3 | 19 132.8 | 0.725 | 9 719.8 | 8 818.8 | 0.165 | |

*P < 0.01, vs. before exposure. DDD, defined daily dose; ICU, intensive care unit. |

2.3 暴露前后两组患者医疗服务利用对比

2.4 暴露前后两组患者医疗费用对比

2.5 姑息治疗对主要结局指标的净影响

表3 姑息治疗对患者各结局指标的净影响值Table 3 The net effect value of palliative care on each outcome |

| Outcomes | Net effect value | |t| | P |

| Drug use | |||

| Average monthly opioid consumption/DDD per person-month | 0.3 | 4.48 | <0.01 |

| Medical service utilization | |||

| Hospital rate/% | -25.6 | 4.53 | <0.01 |

| ICU rate/% | -4.9 | 3.17 | <0.01 |

| Operation rate/% | -14.5 | 4.02 | <0.01 |

| Medical expenditure | |||

| Average monthly total cost/yuan | 2 208.8 | 1.00 | 0.316 |

DDD, defined daily dose; ICU, intensive care unit. |