北京大学学报(医学版) ›› 2020, Vol. 52 ›› Issue (3): 479-485. doi: 10.19723/j.issn.1671-167X.2020.03.013

1990—2010年中国女性早婚和生育的地区不平等性

- 北京大学公共卫生学院,北京大学儿童青少年卫生研究所,北京 100191

Subnational inequalities of early marriage and fertility among Chinese females from 1990 to 2010

Dong-mei LUO,Xiao-jin YAN,Pei-jin HU,Jing-shu ZHANG,Yi SONG( ),Jun MA

),Jun MA

- Institute of Child and Adolescent Health, Peking University, Beijing 100191, China

摘要:

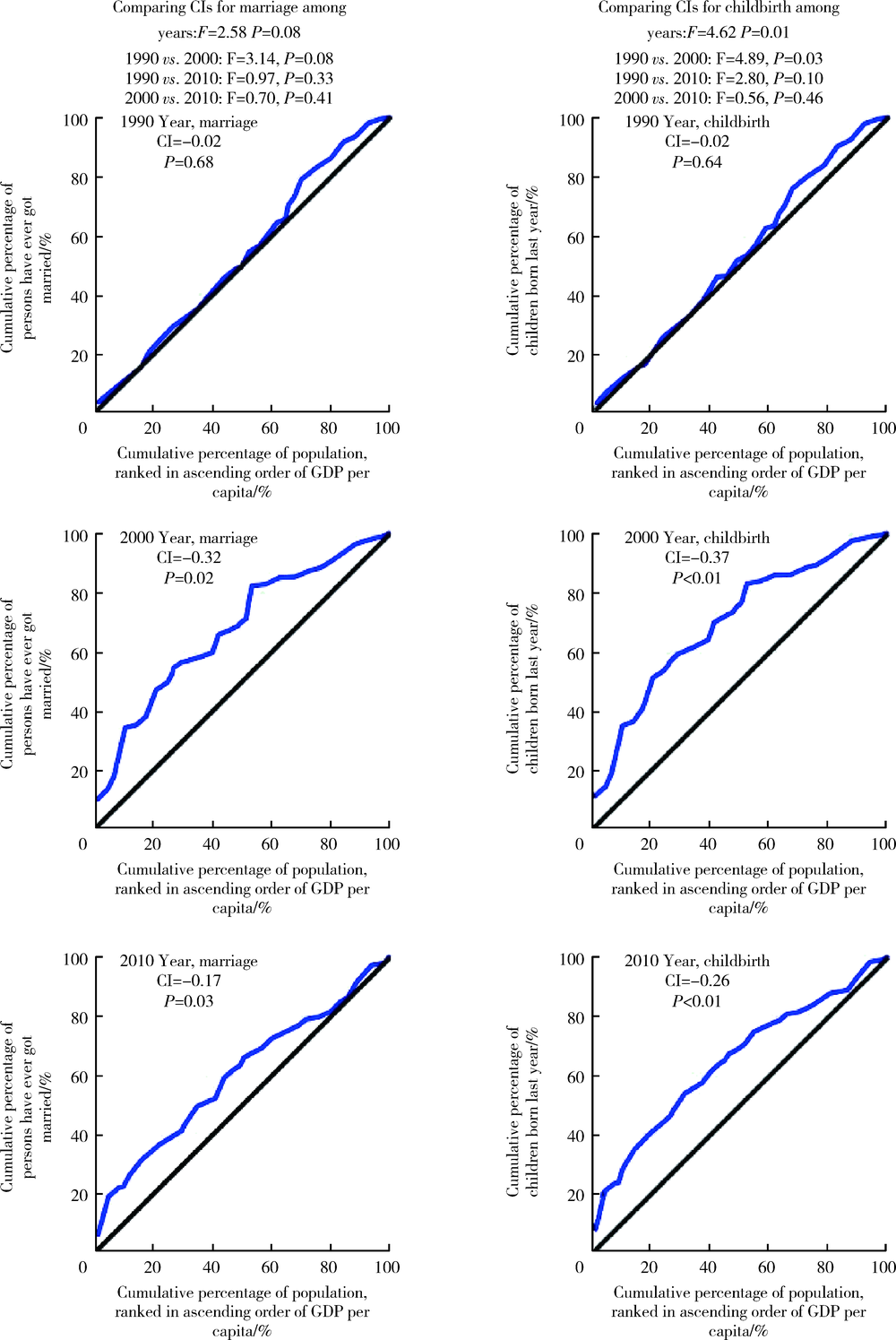

目的 分析1990—2010年中国15~19岁女性青少年结婚和生育的地区不平等性。方法 利用1990—2010年三次全国人口普查汇总数据,计算中国15~19岁女性青少年的已婚率和生育率。将各省份人均国内生产总值(gross domestic product,GDP)作为社会经济发展水平指标,计算女性青少年已婚率和生育率的不平等绝对指数(slope index of inequality,SII)和集中指数(concentration index,CI),并建立线性回归模型衡量已婚率和生育率与人均GDP的关联。结果 1990—2000年,全国15~19岁女性的已婚率从4.7%下降至1.2%,但在2010年反弹至2.1%。生育率从1990年的22.0/1 000人下降至2000年的6.0/1 000人,2010年进一步下降为5.9/1 000人。1990年,15~19岁女性青少年已婚率和生育率地区层面的社会经济不平等性不具有统计学意义(SII和CI均P>0.05)。SII分析显示,2000和2010年,人均GDP最低人群的已婚率比最高人群分别高2.4%(95%CI:0.4~4.4)和2.3%(95%CI:0.3~4.2)。与此同时, 2000年和2010年人均GDP最低人群的生育率比最高人群分别高12.9/1 000人(95%CI:5.4~20.5)和9.3/1 000人(95%CI:4.6~14.0)。已婚的CI值在2000年和2010年分别为-0.32(P=0.02)和-0.17(P=0.03), 生育的CI值在2000年和2010年分别为-0.37(P<0.01)和-0.26(P<0.01)。2000年,人均GDP上升100%,已婚率平均下降1.4%(95%CI:0.1~2.7),生育率平均下降7.9/1 000人(95%CI:2.9~12.8)。2010年,人均GDP上升100%,已婚率平均下降1.5%(95%CI:0.1~2.9),生育率平均下降6.7/1 000人(95%CI:3.2~10.1)。结论 2000年和2010年存在女性青少年早婚早育地区层面的社会经济不平等性,生活在经济发展水平较低的女性青少年更容易早婚早育;减少收入不公平、增加对贫困地区的教育投资可能是改善早婚早育地区不平等的有效措施。

中图分类号:

- R169.1

| [1] | United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals[EB/OL]. [2019-04-09]. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/gender-equality/. |

| [2] |

Azzopardi PS, Hearps SJC, Francis KL, et al. Progress in adolescent health and wellbeing: tracking 12 headline indicators for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2016[J]. Lancet, 2019,393(10176):1101-1118.

pmid: 30876706 |

| [3] |

Viner RM, Ozer EM, Denny S, et al. Adolescence and the social determinants of health[J]. Lancet, 2012,379(9826):1641-1652.

pmid: 22538179 |

| [4] | Patton GC, Sawyer SM, Santelli JS, et al. Our future: a Lancet commission on adolescent health and wellbeing[J]. Lancet, 2016,387(10036):2423-2478. |

| [5] | 国务院人口普查办公室, 国家统计局人口统计司. 中国1990年人口普查资料(第三册)[M]. 北京: 中国统计出版社, 1993: 98-136, 568. |

| [6] | 国务院人口普查办公室, 国家统计局人口和社会科技统计司. 中国2000年人口普查资料(下册)[M]. 北京: 中国统计出版社, 2002: 1618-1677, 1700. |

| [7] | 国务院人口普查办公室, 国家统计局人口和就业统计司. 中国2010年人口普查资料(下册)[M]. 北京: 中国统计出版社, 2012: 1862-1925, 2036. |

| [8] | 中华人民共和国国家统计局. 国家数据[EB/OL]. [ 2019- 05- 01]. http://data.stats.gov.cn/easyquery.htm?cn=E0103. |

| [9] | Mackenbach JP, Stirbu I, Roskam AJ, et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in health in 22 European countries[J]. N Engl J Med, 2008,358(23):2468-2481. |

| [10] | Mackenbach JP, Kunst AE. Measuring the magnitude of socio-economic inequalities in health: an overview of available measures illustrated with two examples from Europe[J]. Soc Sci Med, 1997,44(6):757-771. |

| [11] |

Wagstaff A, Paci P, Van Doorslaer E. On the measurement of inequalities in health[J]. Soc Sci Med, 1991,33(5):545-557.

pmid: 1962226 |

| [12] | Pamuk ER. Social class inequality in mortality from 1921 to 1972 in England and Wales[J]. Popul Stud, 1985,39(1):17-31. |

| [13] |

Wagstaff A. The bounds of the concentration index when the vari-able of interest is binary, with an application to immunization inequality[J]. Health Econ, 2005,14(4):429-432.

pmid: 15495147 |

| [14] | Marphatia AA, Ambale GS, Reid AM. Women’s marriage age matters for public health: A review of the broader health and social implications in South Asia[J]. Front Public Health, 2017,5:269. |

| [15] | Nguyen PH, Scott S, Neupane S, et al. Social, biological, and programmatic factors linking adolescent pregnancy and early childhood undernutrition: a path analysis of India’s 2016 National Family and Health Survey[J]. Lancet Child Adolesc Health, 2019,3(7):463-473. |

| [16] | Gausman J, Langer A, Austin SB, et al. Contextual variation in early adolescent childbearing: A multilevel study from 33,822 communities in 44 low- and middle-income countries[J]. J Adolesc Health, 2019,64(6):737-745. |

| [17] | 江涛, 刘俊林, 付俊. 云南麻栗坡县猛硐瑶族乡农业人口早婚状况调查[J]. 文山师范高等专科学校学报, 2009,22(4):23-26, 57. |

| [18] |

Chao F, Gerland P, Cook AR, et al. Systematic assessment of the sex ratio at birth for all countries and estimation of national imba-lances and regional reference levels[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2019,116(19):9303-9311.

pmid: 30988199 |

| [19] | Guilmoto CZ. Skewed sex ratios at birth and future marriage squeeze in China and India, 2005—2100[J]. Demography, 2012,49(1):77-100. |

| [20] | Jiang Q, Feldman MW, Li S. Marriage squeeze, never-married proportion, and mean age at first marriage in China[J]. Popul Res Policy Rev, 2014,33:189-204. |

| [21] |

GBD 2017 Population and Fertility Collaborators. Population and fertility by age and sex for 195 countries and territories, 1950—2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017BD 2017 Population and Fertility Collaborators. Population and fertility by age and sex for 195 countries and territories, 1950—2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017[J]. Lancet, 2018,392(10159):1995-2051.

pmid: 30496106 |

| [22] | Santelli JS, Song X, Garbers S, et al. Global trends in adolescent fertility, 1990—2012, in relation to national wealth, income inequalities, and educational expenditures[J]. J Adolesc Health, 2017,60(2):161-168. |

| [23] | 史薇. 中国与瑞典中小学教育经费管理的比较研究[D]. 广西: 广西师范大学教育学部, 2018. |

| [24] | Wang D, Chi G. Different places, different stories: A study of spatial heterogeneity of county-level fertility in China[J]. Demogr Res, 2017,37:493-526. |

| [25] | Morgan SP, Guo ZG, Hayford SR. China's below-replacement fertility: Recent trends and future prospects[J]. Popul Dev Rev, 2009,35(3):605-629. |

| [1] | 谢晓炜,李芬,凌光辉,谢希,许素清,陈谊月. 痛风患者健康教育知识知晓度测量问卷的研制及临床应用[J]. 北京大学学报(医学版), 2022, 54(4): 699-704. |

|

||