北京大学学报(医学版) ›› 2023, Vol. 55 ›› Issue (3): 442-449. doi: 10.19723/j.issn.1671-167X.2023.03.009

应激性血糖升高对重症监护病房患者28 d全因死亡风险的预测价值

- 北京大学公共卫生学院社会医学与健康教育系,北京 100191

Predictive value of stress-induced hyperglycemia on 28 d risk of all-cause death in intensive care patients

Yu-xin WANG,Yu-han DENG,Yin-liang TAN,Bao-hua LIU*( )

)

- Department of Social Medicine and Health Education, Peking University School of Public Health, Beijing 100191, China

摘要:

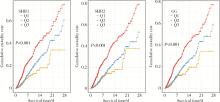

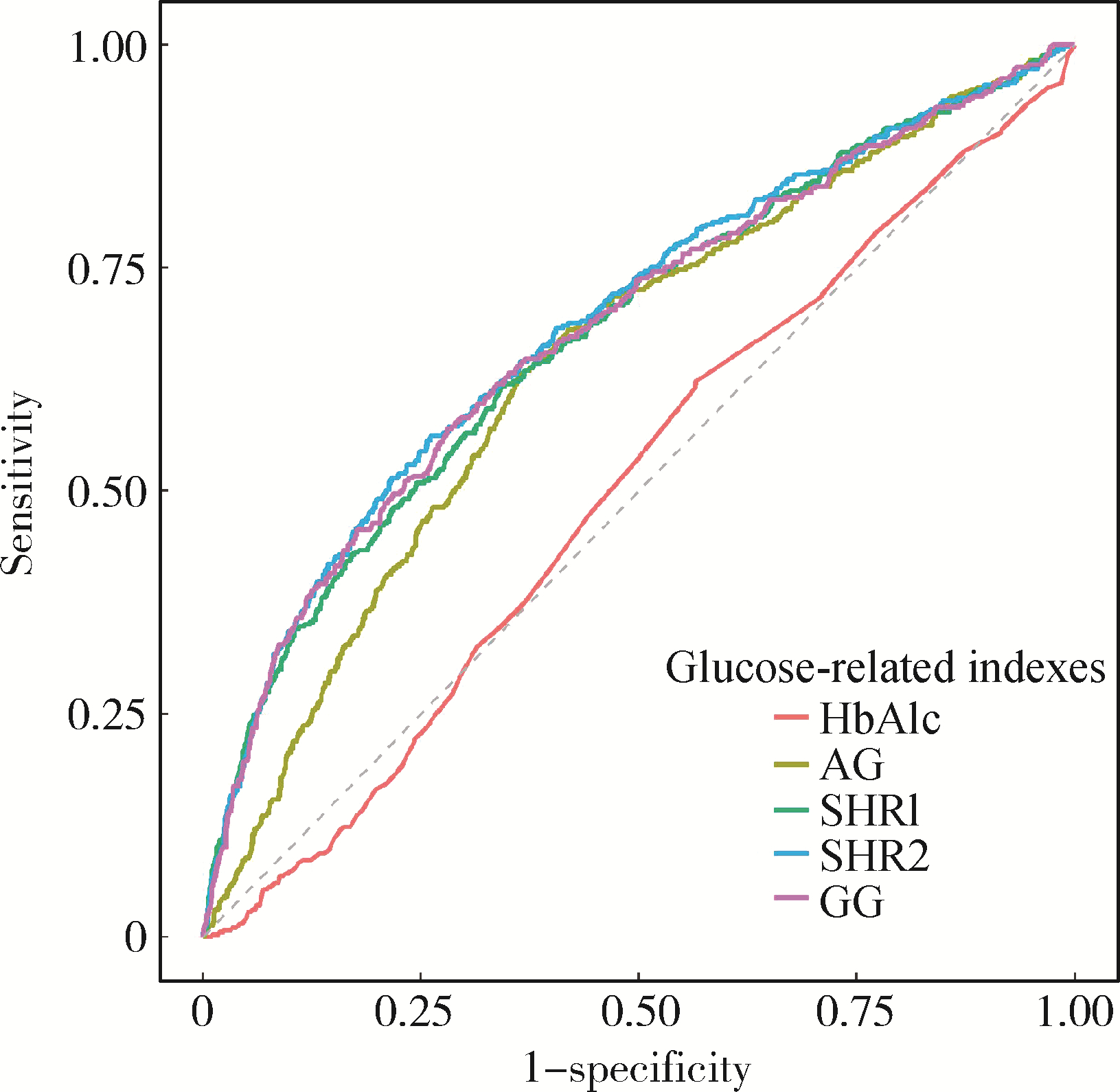

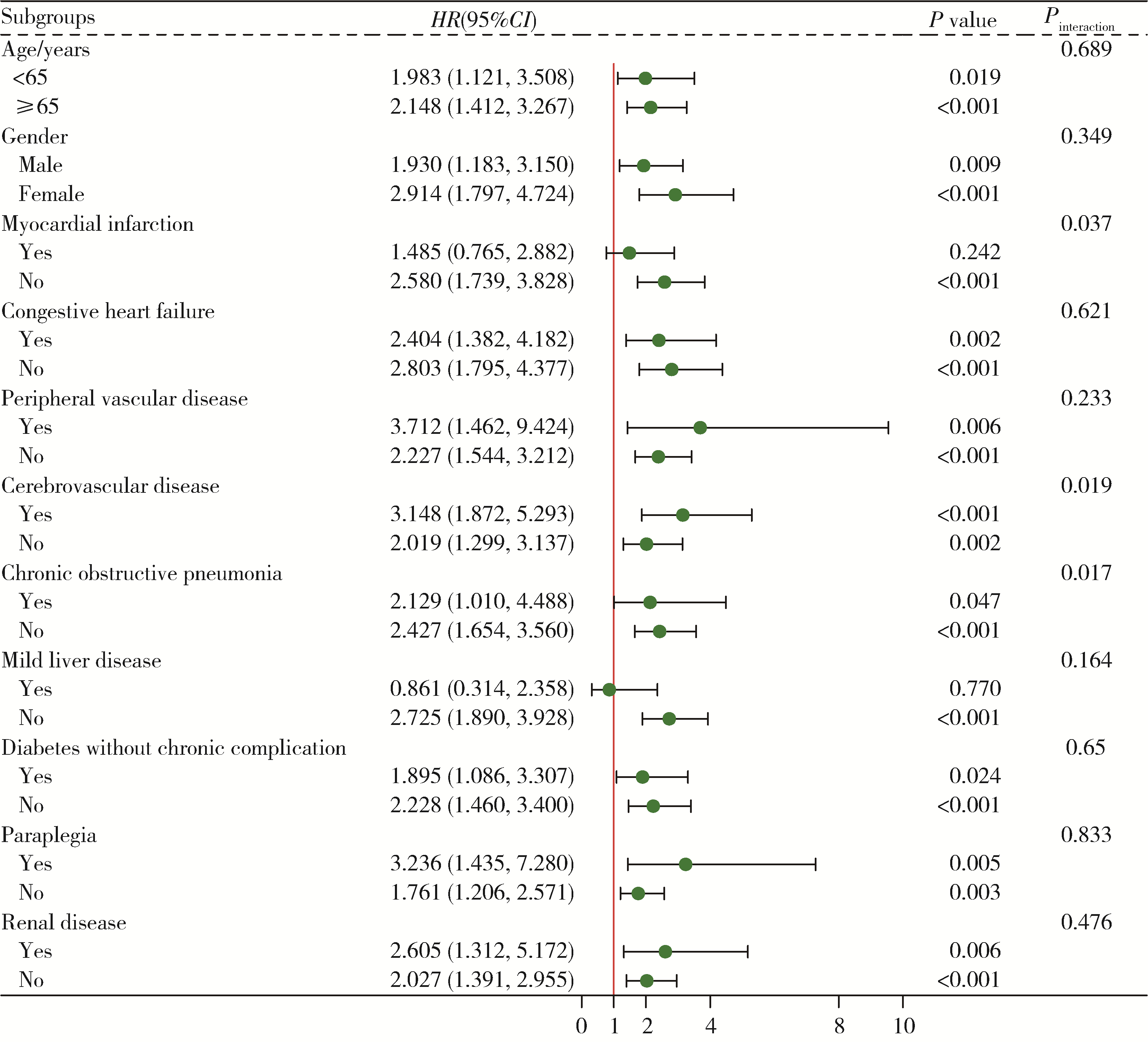

目的: 探究应激性血糖升高与重症监护病房(intensive care unit, ICU) 患者28 d全因死亡风险之间的关系, 并比较不同应激性血糖升高指标的预测效能。方法: 以重症医学(Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care Ⅳ, MIMIC-Ⅳ) 数据库中符合纳入、排除标准的ICU患者为研究对象,将应激性血糖升高指标按照百分位数分为Q1(0~25%)、Q2(>25%~75%)、Q3(>75%~100%)组,以是否发生ICU内死亡及在ICU内接受治疗的时间为结局变量,以人口学特征、实验室指标、合并症等为协变量,利用Cox回归及限制性立方样条探究应激性血糖升高和ICU患者28 d全因死亡风险之间的关联; 采用受试者工作特征(receiver operation characteristic, ROC)曲线下面积(area under curve, AUC)评价不同应激性血糖升高指标的预测效能,应激性血糖升高指标包括应激性血糖升高比值(stress hyperglycemia ratio, SHR) 1、SHR2、血糖间隙(glucose gap, GG); 进一步将应激性血糖升高指标纳入牛津急性疾病严重程度评分(Oxford acute severity of illness score, OASIS),探究其改善评分的预测效能,即采用AUC评估评分区分度,AUC越大表明评分区分度越好,采用Brier score评价评分校准度,Brier score越小,表明评分校准度越好。结果: 共纳入5 249例ICU患者,其中发生ICU内死亡的患者占7.56%。调整混杂因素后的Cox回归分析结果表明,SHR1、SHR2和GG的最高组Q3与最低组Q1相比,ICU患者28 d全因死亡HR(95%CI)分别为1.545(1.077~2.217)、1.602(1.142~2.249)和1.442(1.001~2.061),且随着应激性血糖升高指标的增加,ICU患者死亡风险也逐渐增加(Ptrend < 0.05)。限制性立方样条分析表明,SHR和28 d全因死亡风险之间呈线性关系(P>0.05)。SHR2和GG的AUC显著高于SHR1: AUCSHR2=0.691(95%CI: 0.661~0.720),AUCGG=0.685(95%CI: 0.655~0.714),AUCSHR1=0.680(95%CI: 0.650~0.709),P < 0.05。将SHR2纳入OASIS评分中,能显著提高评分的区分度和校准度:AUCOASIS=0.820(95%CI: 0.791~0.848),AUCOASIS+SHR2=0.832(95%CI: 0.804~0.859),P < 0.05; Brier scoreOASIS=0.071,Brier scoreOASIS+SHR2= 0.069。结论: 应激性血糖升高与ICU患者28 d全因死亡风险密切相关,可为重症监护患者的临床管理和决策提供参考。

中图分类号:

- R193.3

| 1 |

Mousai O , Tafoureau L , Yovell T , et al.Clustering analysis of geriatric and acute characteristics in a cohort of very old patients on admission to ICU[J].Intensive Care Med,2022,48(12):1726-1735.

doi: 10.1007/s00134-022-06868-x |

| 2 |

Dungan KM , Braithwaite SS , Preiser JC .Stress hyperglycaemia[J].Lancet,2009,373(9677):1798-1807.

doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60553-5 |

| 3 |

Harp JB , Yancopoulos GD , Gromada J .Glucagon orchestrates stress-induced hyperglycaemia[J].Diabetes Obes Metab,2016,18(7):648-653.

doi: 10.1111/dom.12668 |

| 4 |

Roberts GW , Quinn SJ , Valentine N , et al.Relative hyperglycemia, a marker of critical illness: Introducing the stress hyperglycemia ratio[J].J Clin Endocrinol Metab,2015,100(12):4490-4497.

doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-2660 |

| 5 |

Liao WI , Wang JC , Chang WC , et al.Usefulness of glycemic gap to predict ICU mortality in critically ill patients with diabetes[J].Medicine (Baltimore),2015,94(36):e1525.

doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001525 |

| 6 |

Lee TF , Drake SM , Roberts GW , et al.Relative hyperglycemia is an independent determinant of in-hospital mortality in patients with critical illness[J].Critical Care Medicine,2020,48(2):e115-e122.

doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004133 |

| 7 |

Mcdonnell ME , Garg R , Gopalakrishnan G , et al.Glycemic gap predicts mortality in a large multicenter cohort hospitalized with covid-19[J].J Clin Endocrinol Metab,2023,108(3):718-725.

doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgac587 |

| 8 |

Xia Z , Gu T , Zhao Z , et al.The stress hyperglycemia ratio, a novel index of relative hyperglycemia, predicts short-term mortality in critically ill patients after esophagectomy[J].J Gastrointest Oncol,2022,13(1):56-66.

doi: 10.21037/jgo-22-11 |

| 9 |

Chen G , Li M , Wen X , et al.Association between stress hyperglycemia ratio and in-hospital outcomes in elderly patients with acute myocardial infarction[J].Front Cardiovasc Med,2021,8,698725.

doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2021.698725 |

| 10 |

Zhu B , Pan Y , Jing J , et al.Stress hyperglycemia and outcome of non-diabetic patients after acute ischemic stroke[J].Front Neurol,2019,10,1003.

doi: 10.3389/fneur.2019.01003 |

| 11 | Guo Y , Wang G , Jing J , et al.Stress hyperglycemia may have higher risk of stroke recurrence than previously diagnosed diabetes mellitus[J].Aging (Albany NY),2021,13(6):9108-9118. |

| 12 | Johnson A, Bulgarelli L, Pollard T, et al. Mimic-Ⅳ documentation (version 1.0)[EB/OL]. (2021-01-01)[2022-10-01]. https://mimic.mit.edu/docs/iv/ |

| 13 |

Koyfman L , Brotfain E , Erblat A , et al.The impact of the blood glucose levels of non-diabetic critically ill patients on their clinical outcome[J].Anaesthesiol Intensive Ther,2018,50(1):20-26.

doi: 10.5603/AIT.2018.0004 |

| 14 |

Olariu E , Pooley N , Danel A , et al.A systematic scoping review on the consequences of stress-related hyperglycaemia[J].PLoS One,2018,13(4):e0194952.

doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0194952 |

| 15 |

Johnson AE , Kramer AA , Clifford GD .A new severity of illness scale using a subset of acute physiology and chronic health evaluation data elements shows comparable predictive accuracy[J].Cri-tical Care Medicine,2013,41(7):1711-1718.

doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31828a24fe |

| 16 |

Su YW , Hsu CY , Guo YW , et al.Usefulness of the plasma glucose concentration-to-HbA1c ratio in predicting clinical outcomes during acute illness with extreme hyperglycaemia[J].Diabetes Metab,2017,43(1):40-47.

doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2016.07.036 |

| 17 |

Allison PD .Multiple imputation for missing data: A cautionary tale[J].Sociol Methods Res,2000,28(3):301-309.

doi: 10.1177/0049124100028003003 |

| 18 |

Murphy AH .A new decomposition of the brier score: Formulation and interpretation[J].Mon Weather Rev,1986,114(12):2671-2673.

doi: 10.1175/1520-0493(1986)114<2671:ANDOTB>2.0.CO;2 |

| 19 |

Nicolau JC , Serrano CV Jr , Giraldez RR , et al.In patients with acute myocardial infarction, the impact of hyperglycemia as a risk factor for mortality is not homogeneous across age-groups[J].Diabetes Care,2012,35(1):150-152.

doi: 10.2337/dc11-1170 |

| 20 |

Merlino G , Pez S , Gigli GL , et al.Stress hyperglycemia in patients with acute ischemic stroke due to large vessel occlusion undergoing mechanical thrombectomy[J].Front Neurol,2021,12,725002.

doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.725002 |

| 21 |

Li W , Ning Y , Ma Y , et al.Association of lung function and blood glucose level: A 10-year study in China[J].BMC Pulm Med,2022,22(1):444.

doi: 10.1186/s12890-022-02208-3 |

| 22 |

Zonneveld TP , Nederkoorn PJ , Westendorp WF , et al.Hyperglycemia predicts poststroke infections in acute ischemic stroke[J].Neurology,2017,88(15):1415-1421.

doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003811 |

| 23 |

Ergul A , Abdelsaid M , Fouda AY , et al.Cerebral neovascularization in diabetes: Implications for stroke recovery and beyond[J].J Cereb Blood Flow Metab,2014,34(4):553-563.

doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2014.18 |

| 24 |

Cai ZM , Zhang MM , Feng RQ , et al.Fasting blood glucose-to-glycated hemoglobin ratio and all-cause mortality among chinese in-hospital patients with acute stroke: A 12-month follow-up study[J].BMC Geriatr,2022,22(1):508.

doi: 10.1186/s12877-022-03203-3 |

| [1] | 袁雯,张奕,陈力,蒋家诺,陈曼曼,刘婕妤,马涛,马奇,崔孟杰,郭桐君,王鑫鑫,董彦会,马军. 儿童青少年身体脂肪分布与抑郁和社交焦虑的关联:基于双能X线检测的横断面研究[J]. 北京大学学报(医学版), 2023, 55(3): 429-435. |

| [2] | 赵亚楠,范慧芸,王翔宇,罗雅楠,张嵘,郑晓瑛. 孤独症患者过早死亡风险及死亡原因[J]. 北京大学学报(医学版), 2023, 55(2): 375-383. |

| [3] | 刘杰,郭超. 正/负性情绪对中国老年人死亡风险影响的前瞻性队列研究[J]. 北京大学学报(医学版), 2022, 54(2): 255-260. |

| [4] | 林瑜,吴静依,蔺轲,胡永华,孔桂兰. 基于集成学习模型预测重症患者再入重症监护病房的风险[J]. 北京大学学报(医学版), 2021, 53(3): 566-572. |

| [5] | 唐雯,高峻逸,马辛宇,张超贺,马连韬,王亚沙. 循环神经网络模型在腹膜透析临床预后预测中的初步应用[J]. 北京大学学报(医学版), 2019, 51(3): 602-608. |

| [6] | 蔺轲,谢俊卿,胡永华,孔桂兰. 支持向量机在ICU急性肾损伤患者住院死亡风险预测中的应用[J]. 北京大学学报(医学版), 2018, 50(2): 239-244. |

|

||